The distinction between, and the connection between, faith and reason is a complicated and extensive subject. A single introductory remark is necessary to eliminate unnecessary misunderstanding from the start.

The point of view presented here is that of a theologian who stands in the Reformation tradition. Within this tradition, faith and reason are distinguished, but not separated. The distinction has to do with the unique subject of theology, namely sin and the redemption of sin through Jesus Christ.

Human reason, thought, philosophy are not necessarily interested in this, and therefore the necessary distinction. However, faith and reason are not separated within this tradition either. Without philosophy, theology has never been able to cope, since people who believe are also people who think, and thinking believers do not want to deal with the reality of life without thinking. Many philosophers are also believers, or are at least interested in certain aspects of theology, and hence also an over-and-over influence.

The starting point of this contribution is summarized programmatically in Martin Luther’s closing speech at the Reichstag of Worms(1) (1521):

“If I do not go through the testimonies of the Scripture and rational arguments cannot be convinced… I remain a prisoner of the Word of God. For this reason I cannot and will not retract anything (of my writings), as it is neither safe nor wholesome to act against your conscience. May God help me, Amen!”

According to Luther, Christian theology is based on biblical statements and rational arguments. A few quotes from the Bible are not enough to tackle life’s challenges. However, rational arguments alone are not sufficient for a peaceful life. The faith in Christ Jesus, which surpasses all rational arguments, lets us share in God’s peace, and protects us from foolishness of thought (Philippians 4:7).

To explain the statement once again: According to philosophy(2), man is a “thinking, sensory-perceivable and bodily being” (Luther, Disputation about man, 1536). To be human and to survive as human, man must use his mind(3). However, the mind and thinking are limited, as they cannot provide answers to all human questions.

Therefore, “man is justified by faith” (Romans 3:28). This means that man has the right to exist before God on the basis of faith in Jesus Christ. Thanks to this “right to exist”, the believer has a share in the ultimate answers to all the dark questions of human existence (1 Corinthians 13:12). This does not absolve the Christian of the duty to deal with the reality at hand thinking, reflecting, studying. The appreciation and gratitude for the (admittedly imperfect) science is part of the Christian’s prayer.

What is meant by “reason”?

The word “reason” is a collective name for quite a few disciplines, such as philosophy as well as the natural sciences. “Reason” (or the German Reason) therefore has to do with knowledge, knowledge, insight and understanding.

When would something be reasonable?

When there is talk of inter-subjective understanding, general validity, verifiability and provability. The playing field of reason therefore has to do with knowledge that can unlock the researchable reality. The search for knowledge and understanding of reality is a challenge that cannot be avoided. We want and must know and try to understand our reality, since our knowledge and insight make a life worth living possible. A life without the sciences and philosophy is (at least within the Western world) unimaginable. A Fundamentalist Biblicism (which is currently enjoying a boom among our people) cannot therefore be satisfactory in the long run.

The critical question is, however, whether the truths of the sciences and the insights of philosophy are sufficient to lead a meaningful existence?

We all know this is not enough, among other things, because today’s certainties can be doubted tomorrow. We also know from experience that our human insights do not provide answers to the most vexing questions: questions such as who and what am I, where do we come from and where are we going? Since we cannot answer the deepest questions of our existence by ourselves, we flee to faith, religion and theology. For some this is nonsensical, but for many others it remains the only way out.

The French philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623 – 1662) rightly said: “The heart has its reasons which the mind does not know.”

What is meant by “faith”?

By “faith” I mean the Christian faith. It has to do with the confidence in the one God who revealed Himself in and through Jesus Christ as the merciful Father who wants to forgive us, our unbelief and ingratitude, and wants to give us a new life.

Faith deprives reason of nothing; nor does it remove reason to make room for itself, since faith is created by the proclamation of the gospel and the operation of the Holy Spirit. Faith is therefore not dependent on reason, just as reason is not dependent on faith. The Christian faith is self-sufficient, and does not need to present itself as the “true philosophy” (Justinus the Martyr, 165 AD).

Philosophy should therefore not try to present itself as “Christian philosophy”, since it does not constantly concentrate on the themes of theology and theology cannot make a substantial contribution to the sciences (such as mathematics).

The connection of faith and reason

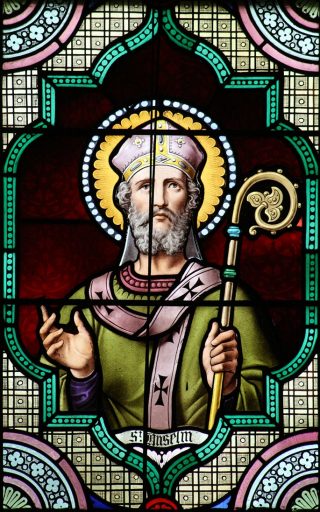

Faith and reason are clearly not the same thing, but neither wants to do without the other. The mutual dependence was classically summarized by Anselm of Canterbury in 1077/8 in the following two slogans: “Faith seeks insight” (“fides quarens intellectum”) and “I believe to be able to know” (“credo ut intelligam“).

What Anselm meant has been debated for hundreds of years now. It seems to me that the following interpretations are held within certain Afrikaner circles: Faith gives us a boost to know and understand reality; and I believe because it is an indispensable element to know and understand reality. The real thing is therefore the philosophy (and with it the sciences), and the faith is a coincidence. With such a point of view, the faith, the theology and the church can be forgotten (and this is what is happening around us)!

To get out of this impasse, it must be accepted that the Christian faith is not a worldview. Faith leaves the understanding of reality to reason (philosophy and the sciences), since the themes of theology cannot make any substantial contribution to scientific knowledge. The contribution that can be made, namely the knowledge of sin, the hope for forgiveness and the desire for gratitude, is worthless information according to the sciences.

However, for more than 2,000 years now, faith and reason have not been able to do without each other. They want to talk to each other.

Thanks to the mutual conversation, they take over each other’s use of language, and the common use of language creates common theme fields. What must always be guarded against is the temptation to prescribe from reason to faith what can be believed and how it must be believed. The Roman scholasticism of the late Middle Ages abused Aristotle to such an extent that the reformers were forced to free theology from an unbiblical doctrine of salvation. Aristotle must be respected and used as an outstanding philosopher. He should not be used to prescribe how the doctrine of salvation should be understood (Luther, Heidelberg Disputation, 1518).

Throughout the ages philosophers have also used biblical concepts and thoughts to build philosophical systems (for example Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope, 1959). When too much is concentrated on biblical statements, such a text loses its philosophical luster. The counterargument could be that philosophy of religion and philosophical theology are fields with a right to exist.

It is therefore clear that faith and reason, theology and philosophy (in the European tradition) are and will remain inextricably linked. However, the challenge will also remain to distinguish faith and reason correctly throughout.

The distinction between faith and reason

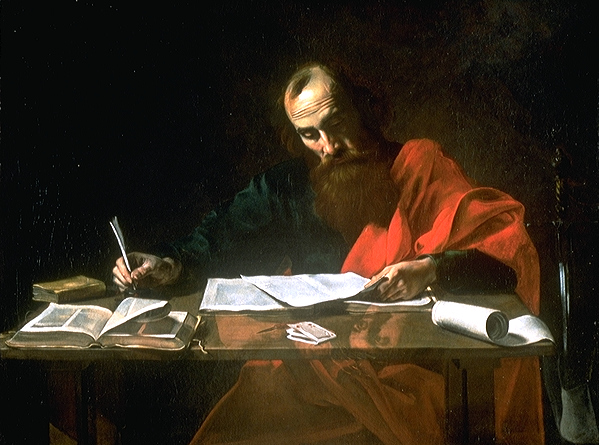

According to Luther, the person who can correctly distinguish between faith and reason is a true theologian. Jesus says in John 7:16: “What I teach is not my own, but comes from him who sent me”. According to Paul (1 Corinthians 1:23), we preach Jesus as the crucified one who is a stumbling block to some and foolishness to others. Christians therefore do not put their trust in the philosophies, but in Christ who was raised from the dead.

Anyone who wants to make a philosophy out of this is welcome, but the gospel is not a philosophy after all. However, those in the church who do not want to learn about philosophy will remain speechless and lack insight into the reality of life of which the members are an inseparable part.

Necessary mutual influence

The conversation between philosophy and theology is an essential one. Philosophy tells how people understand the world today. The gospel must be preached to these, and not other people. Without knowledge and understanding of people’s understanding of reality, theology cannot develop and faith will stagnate.

Faith and theology, however, in the light of the description of reality, give their own perspective on our life reality. Faith and theology do not repeat what the world knows, but explain what the world does not know. Likewise, philosophy must not repeat what the church knows, but it must continue to explain what the church does not know. In this way, the Afrikaans-speaking society can perhaps be better served.

(1) According to the minutes of the Reichstag, and not according to the baseless legend that reads “Here I stand, I can’t do otherwise”.

(2) Luther refers back to the Pythagorean physician, Alkmaion of Kroton, from the sixth/fifth century BC, who claimed that only man is a thinking being. This statement was again defended in the fourth century BC by Aristotle.

(3) Calvin also knew this, and therefore his great appreciation and love for, among other things, the science of law.